Marty Cagan’s Top Quotes

Published:

Preface

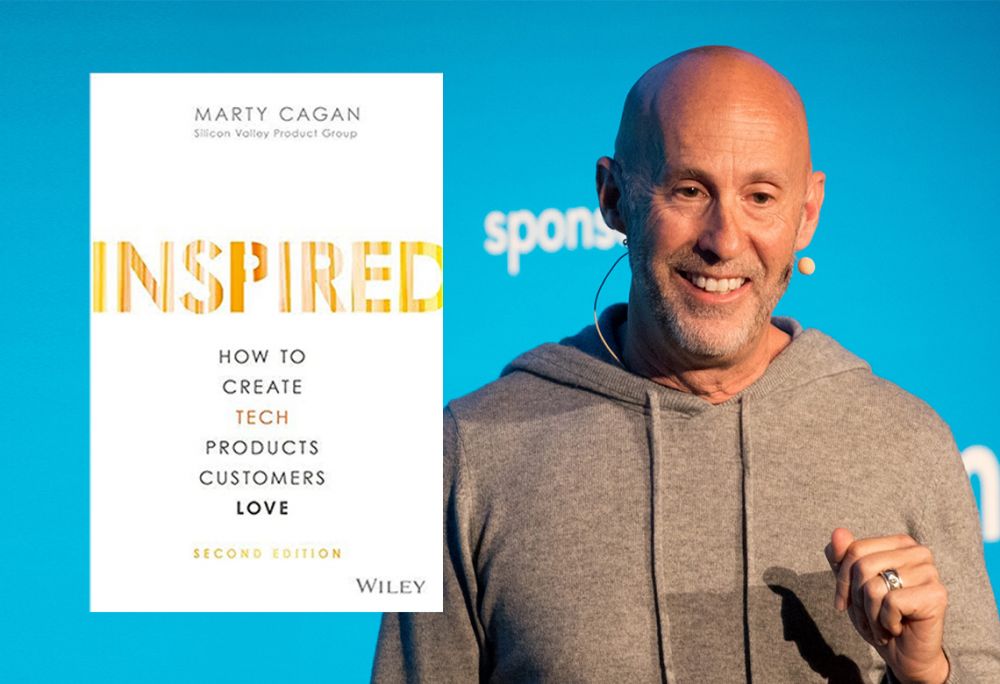

Marty Cagan has been a leader in the product space for decades. He is the founder of the Silicon Valley Product Group and has held leadership roles at Hewlett-Packard, Netscape, and eBay. He is a pillar of the product management industry and has continued to provide leadership through SVPG. Here, I have collected his top quotes from the INSPIRED book.

Marty’s Top Quotes

I loosely define startup as a new product company that has yet to achieve product/market fit

Strong tech‐product companies know they need to ensure consistent product innovation

One of the most critical lessons in product is knowing what we can’t know

The first truth is that at least half of our ideas are just not going to work

Projects are output and product is all about outcome

The biggest flaw of the old waterfall process has always been, and remains, that all the risk is at the end, which means that customer validation happens way too late

In strong teams, product, design, and engineering work side by side, in a give‐and‐take way, to come up with technology‐powered solutions that our customers love and that work for our business

In modern teams, we tackle these risks prior to deciding to build anything. These risks include value risk (whether customers will buy it), usability risk (whether users can figure out how to use it), feasibility risk (whether our engineers can build what we need with the time, skills, and technology we have), and business viability risk (whether this solution also works for the various aspects of our business—sales, marketing, finance, legal, etc.)

The purpose of product delivery is to build and deliver these production‐quality technology products, something you can sell and run a business on

The discovery activities help us determine the necessary product, but it is delivery that actually does the work necessary to build, test, and release the product

While the P in MVP stands for product, an MVP should never be an actual product (where product is defined as something that your developers can release with confidence, that your customers can run their business on, and that you can sell and support). The MVP should be a prototype, not a product

We need teams of missionaries, not teams of mercenaries. Mercenaries build whatever they’re told to build. Missionaries are true believers in the vision and are committed to solving problems for their customers

A big part of the concept of product teams is that they are there to solve hard problems for the business. They are given clear objectives, and they own delivering on those objectives

If the product manager doesn’t have the technology sophistication, doesn’t have the business savvy, doesn’t have the credibility with the key executives, doesn’t have the deep customer knowledge, doesn’t have the passion for the product, or doesn’t have the respect of their product team, then it’s a sure recipe for failure

When a product succeeds, it’s because everyone on the team did what they needed to do. But when a product fails, it’s the product manager’s fault

Successful products are not only loved by your customers, but they work for your business

The successful product manager must be the very best versions of smart, creative, and persistent

In product companies, it is critical that the product manager also be the product owner

Rather than being measured on the output of their design work, the product designer is measured on the success of the product

We need design—not just as a service to make our product beautiful—but to discover the right product

There’s probably no more important relationship for a successful product manager than the one with your engineers

Modern product marketing managers represent the market to the product team—the positioning, the messaging, and a winning go‐to‐market plan. They are deeply engaged with the sales channel and know their capabilities, limitations, and current competitive issues

Data analysts help teams collect the right sort of analytics, manage data privacy constraints, analyze the data, plan live‐data tests, and understand and interpret the results

One of the big challenges of growth is knowing how the whole product hangs together. Some people like to think of holistic view as connecting the dots between the teams

The single most important responsibility of any VP product is to develop a strong team of product managers

The product vision is what drives and inspires the company and sustains the company through the ups and downs

A strong product culture means that the team understands the importance of continuous and rapid testing and learning

Even with the greatest product ideas, if you can’t build and launch your product, it remains just an idea

We encourage you to keep an eye on the participation of the engineering organization in product discovery (both duration and coverage) and follow the frequency of innovations credited to the engineering participant

In growth‐stage and enterprise companies, many product managers complain that they have to spend far too much of their time doing project management activities.

One of the most difficult issues facing every product organization at scale is just how to split up your product across your many product teams

The product vision describes where we as an organization are trying to go, and the product strategy describes the major milestones to get there

The minimum size for a product team is usually two engineers and a product manager, and if the team is responsible for user‐facing technology, then a product designer is needed, too. Fewer than that is considered below critical mass for a product team

Aligning with the user and customer has very real benefits for the product and for the team

One of the absolute hardest assignments in our industry is to try to cause dramatic change in a large and financially successful company

Realize that typical product roadmaps are all about output. Yet, good teams are asked to deliver business results

I define product roadmap as a prioritized list of features and projects your team has been asked to work on. These product roadmaps are usually done on a quarterly basis, but sometimes they are a rolling three months, and some companies do annual roadmaps

Typical roadmaps are the root cause of most waste and failed efforts in product organizations

Management has fair reasons for wanting product roadmaps:

First, they want to be sure you’re working on the highest‐value things first

Second, they are trying to run a business, which means they need to be able to plan. They want to know when key capabilities will launch so they can coordinate marketing programs, sales force hiring, dependencies with partners, and so on

The first inconvenient truth is that at least half of our product ideas are just not going to work

Sometimes customers just aren’t as excited about this idea as we are, so they choose not to use it or buy it (the value isn’t there)

Sometimes they do want to use it, and they try to use it, but it’s so complicated that it’s simply more trouble than it’s worth, which yields the same result—the users don’t use it (the usability isn’t there)

Sometimes the issue is that the customers might have loved it, but it turns out to be much more involved to build than we first thought, and we simply can’t afford the time and cost to deliver (the feasibility isn’t there)

Sometimes the issue is that we encounter serious legal, financial, or business constraints that block the solution from launch (the business viability isn’t there)

The second inconvenient truth is that, even with the ideas that do prove to be valuable, usable, feasible, and viable, it typically takes several iterations to get the execution of this idea to the point where it delivers the expected business value that management was hoping for. This is often referred to as time to money

I view product discovery as the most important core competency of a product organization

If we can prototype and test ideas with users, customers, engineers, and business stakeholders in hours and days—rather than in weeks and months—it changes the dynamics, and most important, the results

The product teams need to have the necessary business context. They need to have a solid understanding of where the company is heading, and they need to know how their particular team is supposed to contribute to the larger purpose

The product vision and strategy: This describes the big picture of what the organization as a whole is trying to accomplish and what the plan is for achieving that vision

The business objectives: This describes the specific, prioritized business objectives for each product team

The idea behind business objectives is simple enough: tell the team what you need them to accomplish and how the results will be measured, and let the team figure out the best way to solve the problems

It is management’s responsibility to provide each product team with the specific business objectives they need to tackle

In outcome‐based roadmaps, each item is stated as a business problem to solve rather than the feature or project that may or may not solve it

Outcome‐based roadmaps are essentially equivalent to using a business objective–based system such as the OKR system

The product vision describes the future we are trying to create, typically somewhere between two and five years out. For hardware or device‐centric companies, it’s usually five to 10 years out

Its primary purpose is to communicate this vision and inspire the teams (and stakeholders, investors, partners—and, in many cases, prospective customers) to want to help make this vision a reality

The product strategy is our sequence of products or releases we plan to deliver on the path to realizing the product vision

For most types of businesses, I encourage teams to construct product strategy around a series of product/market fits

For business‐focused companies, you might have each product/market fit focus on a different vertical market (e.g., financial services, manufacturing, automotive)

For consumer‐focused companies, we often structure each product/market fit around a different customer or user persona

The difference between vision and strategy is analogous to the difference between good leadership and good management. Leadership inspires and sets the direction, and management helps get us there

Most important, the product vision should be inspiring, and the product strategy should be focused

You can make any product vision meaningful if you focus on how you genuinely help your users and customers

Don’t try to please everyone in a single release. Focus on one new target market, or one new target persona, for each release

The vision is meant to inspire the organization, but the organization ultimately is there to come up with solutions that deliver on the business strategy

Remember that customers rarely leave us for our competitors. They leave us because we stop taking care of them

Where the product vision describes the future you want to create, and the product strategy describes your path to achieving that vision, the product principles speak to the nature of the products you want to create

Product principles are not a list of features, and they are not tied to any one product release. The principles are aligned with the product vision for an entire product line

In OKR, Key results should be a measure of business results, not output or tasks

OKRs become an increasingly necessary tool for ensuring that each product team understands how they are contributing to the greater whole, coordinating work across teams, and avoiding duplicate work

If you deploy OKRs for your product organization, the key is to focus your OKRs at the product team level

When using OKRs at scale, there’s a larger burden on leadership and management to ensure that the organization is truly aligned, that each and every product team understands how they fit into the mix, and that they are there to contribute

Much of the key to effective product discovery is getting access to our customers without trying to push our quick experiments into production

If you want to discover great products, it really is essential that you get your ideas in front of real users and customers early and often. If you want to deliver great products, you want to use best practices for engineering and try not to override the engineers’ concerns

The purpose of product discovery is to address these critical risks:

Will the customer buy this, or choose to use it? (Value risk)

Can the user figure out how to use it? (Usability risk)

Can we build it? (Feasibility risk)

Does this solution work for our business? (Business viability risk)

One of the most common traps in product is to believe that we can anticipate our customer’s actual response to our products. We know today that we must validate our actual ideas on real users and customers. We need to do this before we spend the time and expense to build an actual product, and not after

Our goal in discovery is to validate our ideas the fastest, cheapest way possible

We need to validate the feasibility of our ideas during discovery, not after. We need to ensure the feasibility before we decide to build, not after. We need to validate the business viability of our ideas during discovery, not after

It is absolutely critical to ensure that the solution we build will meet the needs of our business before we take the time and expense to build out that product

One of the keys to having a team of missionaries rather than a team of mercenaries is that the team has learned together

In general, product discovery is about tackling risks around value, usability, feasibility, and business viability. However, in some cases, there’s an additional risk: ethics

I encourage product teams to consider the ethical implications of their solutions, too. When a significant ethical risk is identified, see if you can’t find alternative solutions that solve the problem in a way that doesn’t have negative consequences

Most product teams normally think of an iteration as a delivery activity. If you release weekly, you think in terms of one‐week iterations

Framing techniques help us to quickly identify the underlying issues that must be tackled during product discovery

Sadly, it’s not enough to create a product or solution that our customers love, that is usable, and that our engineers can deliver. The product also must work for our business. This is what it means to be viable

But one of the most important lessons in our industry is to fall in love with the problem, not the solution

The idea is to answer four key questions about the discovery work you are about to undertake:

What business objective is this work intended to address? (Objective)

How will you know if you’ve succeeded? (Key results)

What problem will this solve for our customers? (Customer problem)

What type of customer are we focused on? (Target market)

We can use story map to frame our prototypes, and then as we get feedback on our prototypes and learn how people interact with our product ideas, we can easily update the story map to serve as a living reflection of the prototypes. As we finalize our discovery work and progress into delivery, the stories from the map move right into the product backlog

Let’s be clear about what it means to be a reference customer: This is a real customer (not friends or family), who is running your product in production (not a trial or prototype), who has paid real money for the product (it wasn’t given away to entice them to use it), and, most important, who is willing to tell others how much they love your product (voluntarily and sincerely).

We are discovering and developing a set of reference customers in parallel with discovering and developing the actual product

Product/market fit shows up in terms of happier customers, lower churn rates, shortened sales cycles, and rapid organic growth

One of the most common techniques for assessing product/market fit is known as the Sean Ellis test. This involves surveying your users (those in your target market that have used the product recently, at least a couple times, and you know from the analytics that they’ve at least made it through to the core value of the product) and asking them how they’d feel if they could no longer use this product. The general rule of thumb is that if more than 40 percent of the users would be “very disappointed,” then there’s a good chance you’re at product/market fit

Remember product/market fit does not mean that you are done with working on that product

A concierge test is a relatively new name to describe an old but effective technique. The idea is that we do the customer’s job for them—manually and personally

A concierge test requires going out to the actual users and customers and asking them to show you how they work so that you can learn how to do their job, and so that you can work on providing them a much better solution

I consider developers to be one of the consistently best sources of truly innovative product ideas. Developers are in the best position to see what’s just now possible, and so many innovations are powered by these insights.

The overarching purpose of any form of prototype is to learn something at a much lower cost in terms of time and effort than building out a product

The primary purpose of a prototype is to tackle one or more product risks (value, usability, feasibility, or viability) in discovery; however, in many cases, the prototype goes on to provide a second benefit, which is to communicate to the engineers and the broader organization what needs to be built. This is often referred to as prototype as spec

The amount of time the feasibility prototype is estimated to take comes from the engineers, but whether or not the team takes that time depends on the product manager’s judgment call as to whether it’s worth pursuing this idea

A user prototype—one of the most powerful tools in product discovery—is a simulation. Smoke and mirrors. It’s all a façade

A user prototype is key to several types of validation and is also one of our most important communication tools

The big limitation of a user prototype is that it’s not good for proving anything—like whether or not your product will sell

A Wizard of Oz prototype combines the front‐end user experience of a high‐fidelity user prototype but with an actual person behind the scenes performing manually what would ultimately be handled by automation

We think of four types of questions we’re trying to answer during discovery:

Will the user or customer choose to use or buy this? (Value)

Can the user figure out how to use this? (Usability)

Can we build this? (Feasibility)

Is this solution viable for our business? (Business viability)

In product discovery, we’re essentially trying to quickly separate the good ideas from the bad as we work to try to solve the business problems assigned to us

We usually do usability testing with a high‐fidelity user prototype. You can get some useful usability feedback with a low‐ or medium‐fidelity user prototype, but for the value testing that typically follows usability testing, we need the product to be more realistic (more on why later)

Just because someone can use our product doesn’t mean they will choose to use our product

Customers don’t have to buy our products, and users don’t have to choose to use a feature. They will only do so of they perceive real value

The customer must perceive your product to be substantially better to motivate them to buy your product and then wade through the pain and obstacles of migrating from their old solution

The most common type of qualitative value testing is focused on the response, or reaction. Do customers love this?

For many products, we need to test efficacy, which refers to how well this solution solves the underlying problem. In some types of products, this is very objective and quantitative

One of the biggest possible wastes of time and effort, and the reason for countless failed startups, is when a team designs and builds a product, yet, when they finally release the product, they find that people won’t buy it

The demand‐testing technique is called a fake door demand test. The idea is that we put the button or menu item into the user experience exactly where we believe it should be. But, when the user clicks that button, rather than taking the user to the new feature, it instead takes the user to a special page that explains that you are studying the possibility of adding this new feature, and you are seeking customers to talk to The demand‐testing technique is called a fake door demand test

One of the real advantages to startups from a product point of view is that there’s no legacy to drag along, no revenue to preserve, and no reputation to safeguard. This allows us to move very quickly and take significant risks without much downside

The most important point for technology companies: If you stop innovating, you will die

Quantitative testing tells us what’s happening (or not), but it can’t tell us why, and what to do to correct the situation

Qualitative testing is not about proving anything. That’s what quantitative testing is for. Qualitative testing is about rapid learning and big insights

I argue that qualitative testing of your product ideas with real users and customers is probably the single most important discovery activity for you and your product team

It’s important to conduct the usability test before the value test, and to do one immediately after the other

Focus groups might be helpful for gaining market insights, but they are not helpful in discovering the product we need to deliver

To test usability and value, the user needs to be able to use one of the prototypes we described earlier. When we’re focused on testing value, we usually utilize high‐fidelity user prototypes. High‐fidelity means it feels very realistic, which turns out to be especially important for value testing. You can also use a live‐data prototype or a hybrid prototype

The main challenge in testing value when you’re sitting face to face with actual users and customers is that people are generally nice—and not willing to tell you what they really think. So, all of our tests for value are designed to make sure the person is not just being nice to you

As product manager, you need to make sure you are at every single qualitative value test. Do not delegate this

While qualitative testing is all about fast learning and big insights, quantitative techniques are all about collecting evidence

A live‐data prototype is one of the forms of prototype created in product discovery intended to expose certain use cases to a limited group of users to collect some actual usage data

The reason we love A/B tests is because the user doesn’t know which version of the product she is seeing. This yields data that is very predictive, which is what we ideally want

Optimization testing is normally surface‐level, low‐risk changes, which we often test in a split test (50:50)

In discovery A/B testing, we usually have the current product showing to 99 percent of our users, and the live‐data prototype showing to only 1 percent of our users or less. We monitor the A/B test more closely

Any capable product manager today is expected to be comfortable with data and understand how to leverage analytics to learn and improve quickly

Today, in the spirit of data beats opinions, we have the option of simply running a test, collecting some data, and then using that data to inform our decisions

However, as powerful as the role of data is for us, the most important thing to keep in mind about analytics is that the data will shine a light on what is happening, but it won’t explain why. We need our qualitative techniques to explain the quantitative results

For most product managers, the first thing they do in the morning is to check the analytics to see what happened during the preceding night

Many of our best product ideas are based on approaches to solving the problem that are only now possible, which means new technology and time to investigate and learn that technology

However, the truth is this is not enough. The solution must also work for your business

I also explain to them that this is often what separates the good product managers from the great ones, and that more than anything else, this is what is really meant by being the CEO of the product

A user test is when we test our product ideas on real users and customers. It is a qualitative usability and value‐testing technique, and we let the user drive. The purpose is to test the usability and value of the prototype or product

A product demo is when you sell your product to prospective users and customers, or evangelize your product across your company. This is a sales or persuasive tool. Product marketing usually creates a carefully scripted product demo, but the product manager will occasionally be asked to give the product demo—especially with high‐value customers or execs. In this case, the product manager does the driving. The purpose is to show off the value of the prototype or product

A walkthrough is when you show your prototype to a stakeholder and you want to make sure they see and note absolutely everything that might be a concern. The purpose is to give the stakeholder every opportunity to spot a problem

A discovery sprint is a one‐week time box of product discovery work, designed to tackle a substantial problem or risk your product team is facing

Discovery coaches are typically former product managers or product designers and they have usually worked for, or with, leading product companies

My view is that product discovery is the most important competency of a new startup, so I believe an effective Lean Startup coach must also be very strong at product

One of the simplest techniques for facilitating moving to new ways of working is the use of pilot teams. Pilot teams allow the roll out of change to a limited part of the organization before implementing it more broadly

Some people in your organization love change, some want to see someone else use it successfully first, some need more time to digest changes, and a few hate change and will only change if they’re forced to do it

One practical test of whether a person is considered a stakeholder is whether or not they have veto power, or can otherwise prevent your work from launching

The product manager has the responsibility to understand the considerations and constraints of the various stakeholders, and to bring this knowledge into the product team

One of the most common mistakes product managers make with stakeholders is that they show them their solution after they have already built it. Commit to previewing your solutions during discovery with the key stakeholders before you put this work on the product backlog

In discovery, you are not only making sure that your solutions are valuable and usable (with customers), and feasible (with engineers), but you are also making sure your stakeholders will support the proposed solution

Good teams have a compelling product vision that they pursue with a missionary‐like passion. Bad teams are mercenaries

Good teams get their inspiration and product ideas from their vision and objectives, from observing customers’ struggle, from analyzing the data customers generate from using their product, and from constantly seeking to apply new technology to solve real problems. Bad teams gather requirements from sales and customers

Good teams are skilled in the many techniques to rapidly try out product ideas to determine which ones are truly worth building. Bad teams hold meetings to generate prioritized roadmaps

Good teams have product, design, and engineering sit side by side, and they embrace the give and take between the functionality, the user experience, and the enabling technology. Bad teams sit in their respective silos, and ask that others make requests for their services in the form of documents and scheduling meetings

Good teams ensure that their engineers have time to try out the prototypes in discovery every day so that they can contribute their thoughts on how to make the product better. Bad teams show the prototypes to the engineers during sprint planning so they can estimate

Good teams engage directly with end users and customers every week, to better understand their customers, and to see the customer’s response to their latest ideas. Bad teams think they are the customer

Good teams know that many of their favorite ideas won’t end up working for customers, and even the ones that could will need several iterations to get to the point where they provide the desired outcome. Bad teams just build what’s on the roadmap, and are satisfied with meeting dates and ensuring quality

Good teams obsess over their reference customers. Bad teams obsess over their competitors

Good teams celebrate when they achieve a significant impact to the business results. Bad teams celebrate when they finally release something

I define consistent innovation as the ability of a team to repeatedly add value to the business

Organizations that lose the ability to innovate at scale are inevitably missing one or more of the following attributes

Customer‐centric culture

Compelling product vision

Focused product strategy

Strong product managers

Stable product teams

Engineers in discovery

Corporate courage

Empowered product teams

Product mindset

Time to innovate

In an IT‐mindset organization, the product teams exist to serve the needs of the business. In contrast, in a product‐mind set organization, the product teams exist to serve the company’s customers in ways that meet the needs of the business

The lack of a strong and capable product manager is typically a major reason for slow product

I think of product culture along two dimensions. The first dimension is whether the company can consistently innovate to come up with valuable solutions for their customers. This is what product discovery is all about. The second dimension is execution. It doesn’t matter how great the ideas are if you can’t get a productized, shippable version delivered to your customers. This is what product delivery is all about

photo by The Product Hub

Leave a Comment